Unlocking the Secrets of American Corporate Profitability: Why Profit Margins Soar

Decoding the Kalecki-Levy Profit Equation to Navigate Economic Shifts and Policy Impacts

Executive Summary

The Kalecki-Levy profit equation, independently derived by Jerome Levy and Michal Kalecki, is a macroeconomic accounting identity that explains the determinants of corporate profits. The equation states that:

Profits = Net Investment + Dividends – Household Savings – Government Savings – Foreign Savings

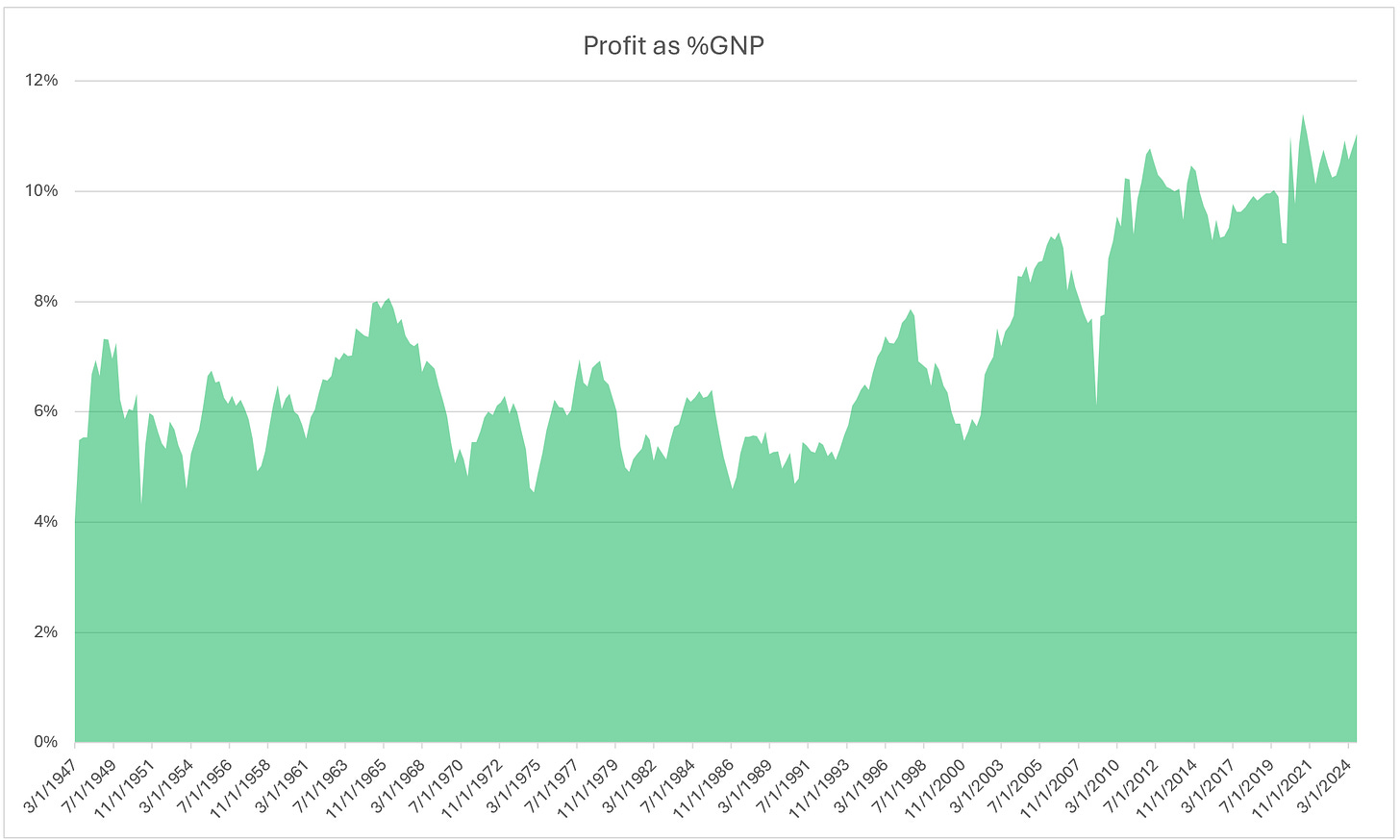

Net Investment: Represents additions to productive capital, currently hovering at 5-6% and boosted by recent government initiatives and AI investments.

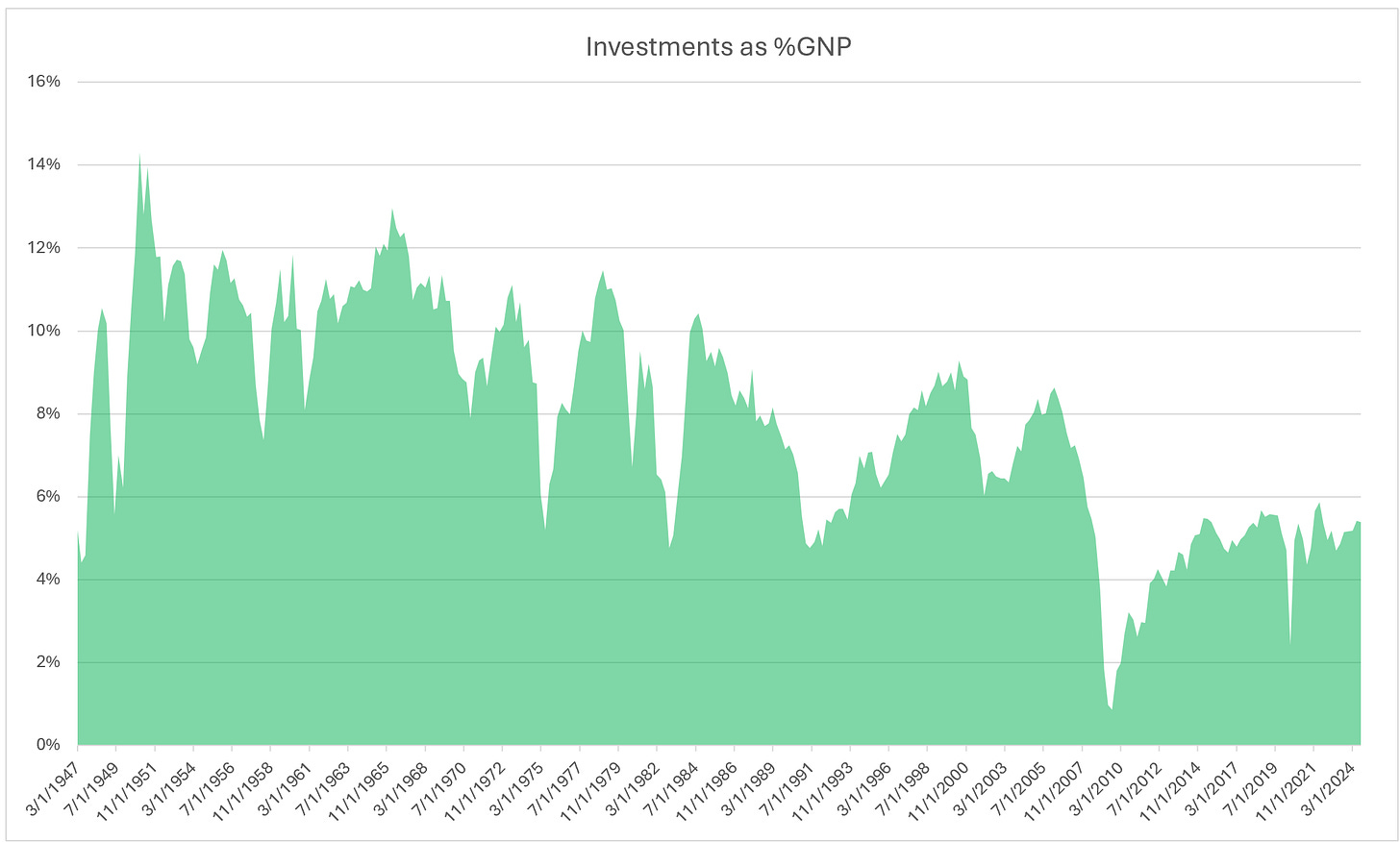

Dividends: Includes stock buybacks and cash payouts, gaining prominence since the 1980s as companies prioritize shareholder returns.

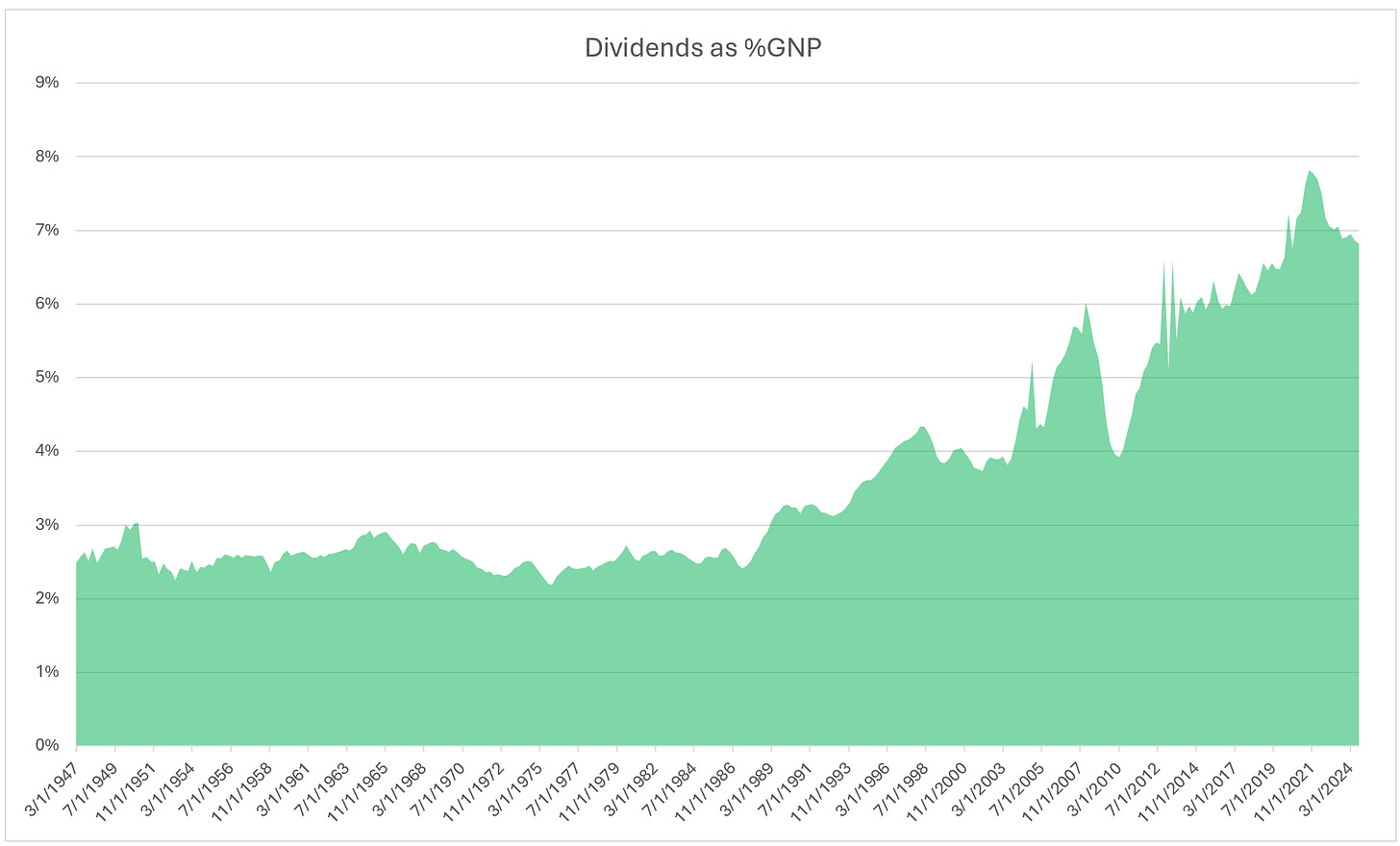

Household Savings: Currently at historically low levels despite recent upward revisions.

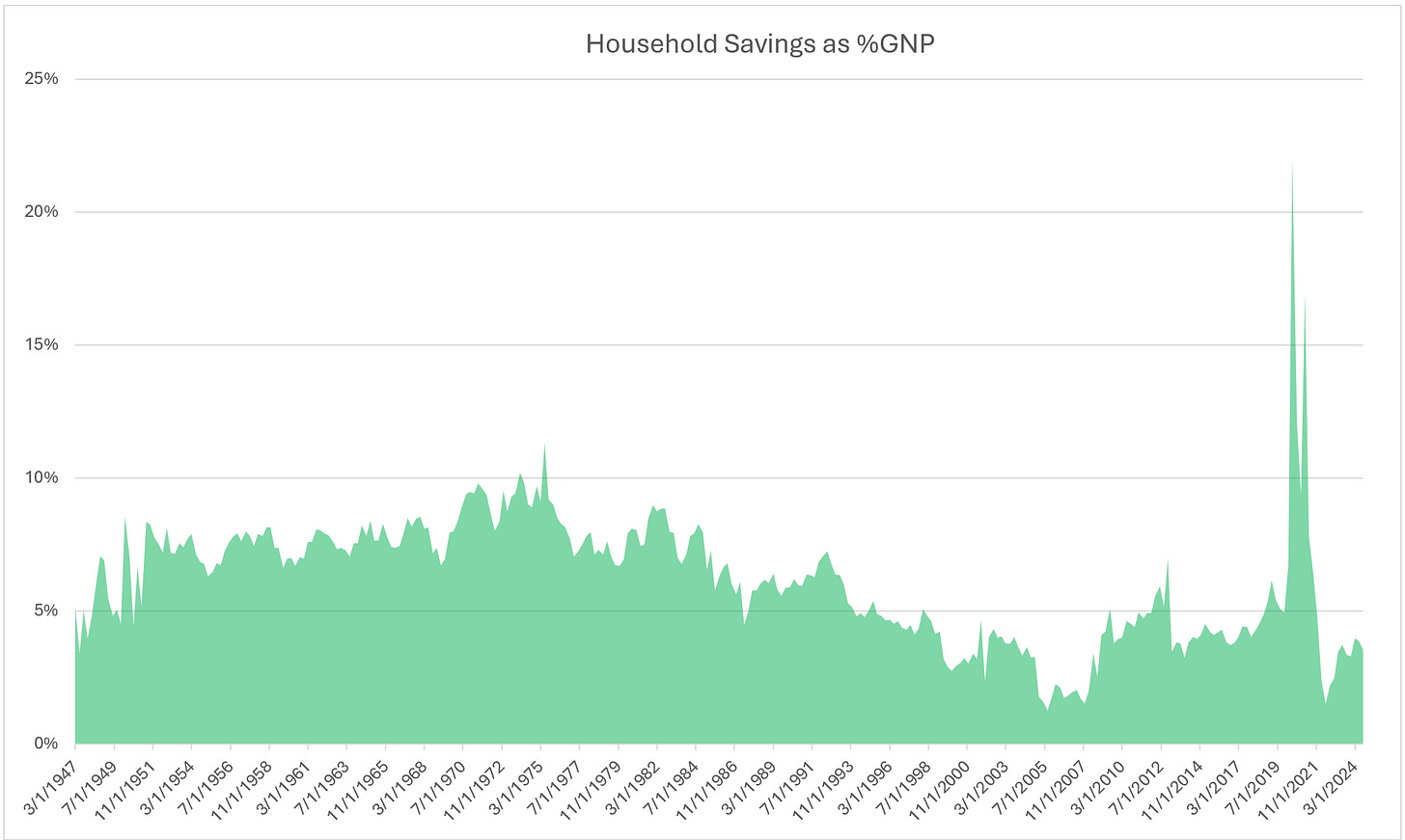

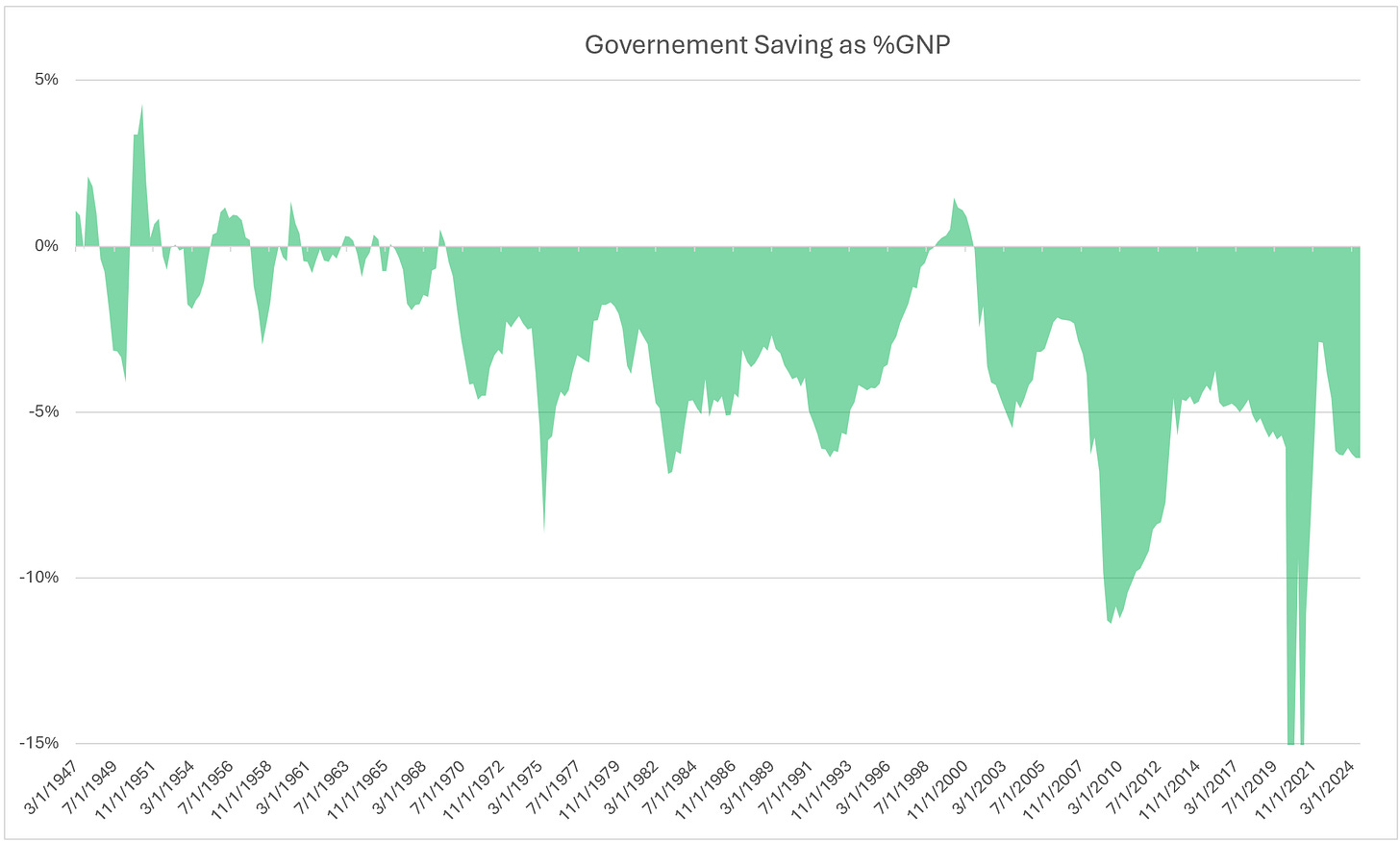

Government Savings: Large deficits have become a dominant profit driver since the 2008 financial crisis.

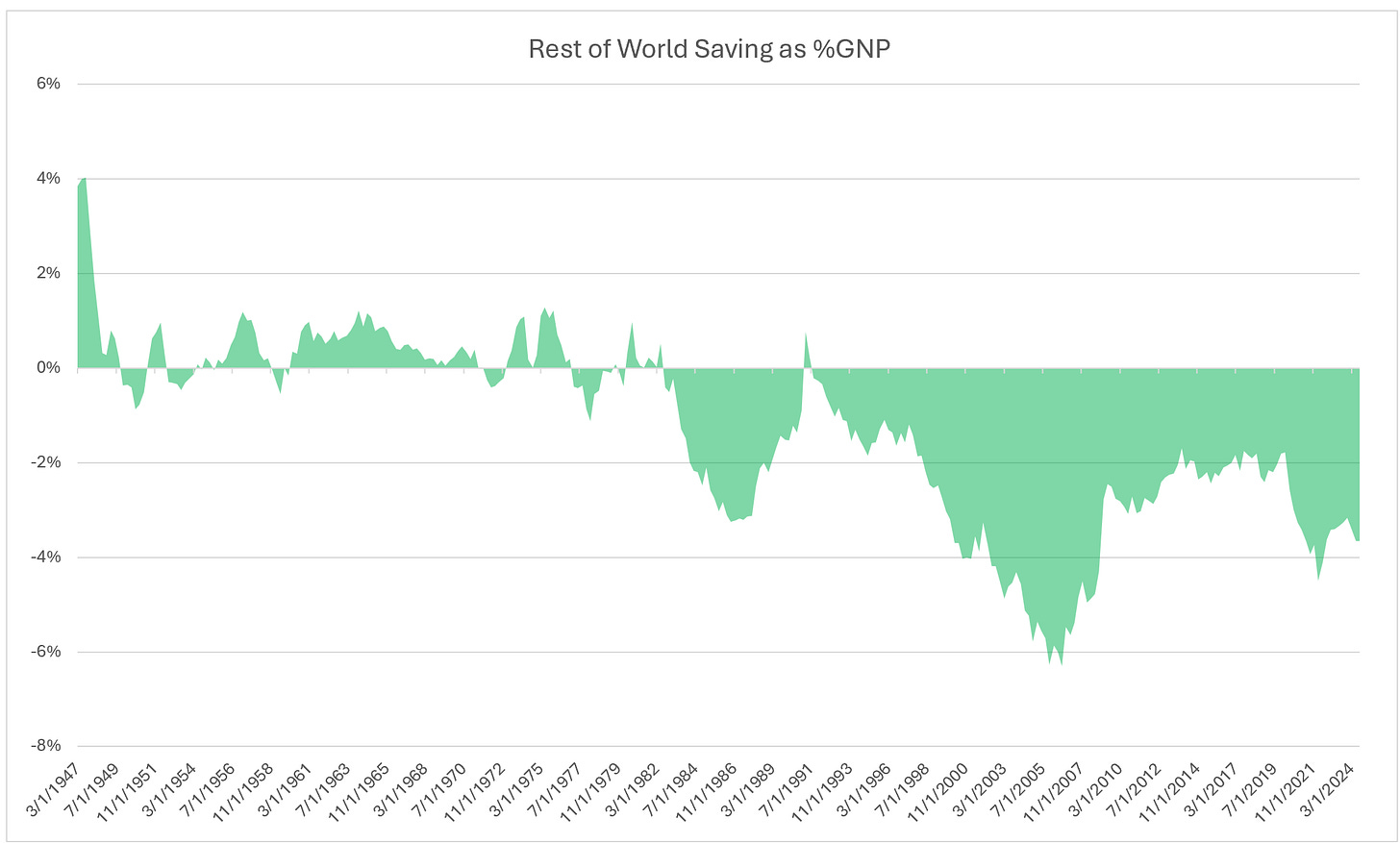

Foreign Savings: Influenced by trade imbalances and potentially overstated due to corporate profit shifting.

This article reviews the historical trends of these components and analyzes the potential impact of Trump's proposed policies, highlighting both opportunities for profit growth and risks of increased economic volatility. It also considers how a recession could alter these dynamics.

Origin

The Kalecki-Levy profit equation links corporate profits to macroeconomic flows. Jerome Levy (1908) and Michal Kalecki (1930s) arrived at this formulation independently, offering unique perspectives:

Levy, an American economist, focused on practical business observations, coining the term "economic machine" to describe monetary flows.

Kalecki, a Polish economist with Marxist inclinations, emphasized systemic relationships and included government and foreign sectors in his analysis.

This framework remains a cornerstone for understanding profit dynamics in modern economies. The Kalecki-Levy equation can be expressed as:

Profits = Net Investment + Dividends – Household Savings – Government Savings – Foreign Savings

1. Net Investment

Definition: This is gross investment minus depreciation. It represents the actual addition to the productive capital stock of the economy.

Note that in national income accounting (e.g., BEA data in the U.S.), spending on R&D, software, and certain intellectual property is treated as capital investment and included in net investment. This adjustment helps better reflect the role of intangibles in economic production. As you probably know this is not the case under GAAP, where spending on intangible assets like R&D is often expensed rather than capitalized, especially for internally generated intangibles. This treatment understates the long-term productive value of these expenditures in corporate financial statements.

Impact: Investment is a direct inflow to corporate profits. When businesses invest, it stimulates economic activity by creating income for other firms.

Intuition: Imagine a factory upgrading its equipment. The expenditure flows to equipment manufacturers, generating profits for them.

Historical Trend: Investment was the dominant driver of profits during post-war reconstruction and industrial expansion (1950–1970s). It collapsed during the 2008 GFC and is howering at 5-6% in recent years.

Where would it be without the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act (March 2021), the American Rescue Plan (November 2021), the CHIPS and Science Act (August 2022), the Inflation Reduction Act (August 2022) and the recent AI CapEx boom?

2. Dividends

Definition: Payments to shareholders as a share of corporate earnings. This includes both stock buybacks and cash payouts to shareholders.

Impact: While dividends reduce corporate retained earnings, they contribute to profits indirectly by boosting household income, which can lead to increased consumption.

Intuition: A company pays dividends, which households spend on goods, boosting revenues for other firms.

Historical Trend: Dividends gained prominence as companies shifted focus from reinvestment to rewarding shareholders, especially after the 1980s.

In less competitive markets, firms can extract higher profits due to their increased market power.

This allows them to maintain higher prices and profit margins, potentially leading to what economists consider "economic rents".

In this context, dividends could be seen as a form of rent extraction, particularly when they result from market power rather than genuine value creation or innovation.

Higher dividends, when viewed as rent extraction, contribute positively to corporate profits in the equation, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

This situation might lead to decreased pressure for productive investment, as firms can maintain profitability through market power rather than innovation or expansion.

3. Household Savings

Definition: The portion of household income not spent on consumption.

Impact: High savings reduce aggregate demand, leading to lower revenues and profits for firms.

Intuition: If households save more and spend less, businesses sell fewer goods, reducing their profits.

Historical Trend: Household savings fell during the late 20th century, driven by easy credit and rising consumer debt. However, savings temporarily spiked during economic crises, such as the 2008 recession and the COVID-19 pandemic with the government generous handouts. Household savings rate was recently revised sharply upward but remains historically low.

4. Government Savings

Definition: Government surpluses (savings) or deficits (dissaving).

Impact: Fiscal deficits boost corporate profits by injecting spending into the economy, while surpluses reduce profits.

Intuition: During a government stimulus, public funds flow into businesses via contracts or consumer subsidies, increasing corporate revenues.

Historical Trend: Government deficits have become a dominant profit driver since the 2008 financial crisis, surpassing historical norms. While historically deficit were counter cylical, today’s deficit, in a booming economy, surpass the recession (except for the 2008 GFC) deficit of the past.

This trend suggests the potential arrival of "Big Government," as Hyman Minsky predicted, where government plays a more active role in the economy.

5. Foreign Savings

Definition: Net savings of foreign entities, equivalent to the domestic current account deficit.

Impact: Current account deficits (foreign dissaving) boost domestic profits by increasing demand for exports.

Intuition: A foreign country buys more goods from domestic businesses than it sells, transferring income to the domestic corporate sector.

Historical Trend: Foreign savings grew in importance with globalization and trade imbalances, particularly in the late 20th century.

The Fracking revolution contributed to a meaningful reduction in the current account deficit. It has increased again in recent years, partly due to a strong USD and an aggressive policy of exporting excess capacity from China.

However, the sources caution that the officially reported current account deficit might be overstated due to corporate profit shifting. Many multinational U.S. corporations employ strategies to shift their profits to low-tax havens or foreign affiliates. This practice can artificially inflate the reported trade deficit, as profits earned abroad are not fully captured in domestic accounting.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stocks, Quants, and Global Market Shocks to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.